InDel paper and musings on alignments

After a very windy 5-year+ ordeal*, I’m happy to say that we have finally published the paper covering the most successful part of my PhD work! Four years since the original preprint is a very long time and it seems hard to understand how it could have taken this long, so I’ll rattle off a few numbers to provide some context into the personal sides of academic publishing that rarely get mentioned.

Since the preprint was posted:

- I’ve finished my PhD and worked in 3 different companies.

- I’ve moved between countries 2 times.

- The paper went to 3 different journals, with multiple rounds of reviews.

Dr. Vitor Pinheiro, my PhD supervisor and corresponding author on the paper, had his own personal/career transitions in this period that were lower in count, but just as impactful. Refer to his own blog post from last year explaining some of the challenges he faced moving the lab to Belgium.

This post is actually meant to discuss some aspects of the paper, but I felt it was worth adding this comment at the beginning to give more people a view into the black box of the world of papers and journals. I was fortunate to have continued progressing in my career despite not having a first-author publication from the PhD until now, but I am very aware that not all roads I could have taken would have been so forgiving of this gap.

The work

The paper describes our InDel framework for tuneable construction of high-quality DNA libraries containing diversity in length and composition, coupled with an alignment-free strategy to analyse the results of selection experiments using those libraries. Vitor already wrote a very nice post on the reasons why we think the assembly approach is relevant, so I’m going to focus on the analysis strategy. I’ll cover how we landed on the idea and then mention some more recent developments in the field that I think provide support for our attempt to avoid alignments altogether.

Before generating any experimental sequencing data for this work, we realised that the standard approach of building Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA) to compare homologous residues in different sequences would not work for our length-variant libraries of ~5-10 residues. In the absence of structural or evolutionary information to inform how residues should be placed into MSA columns, non-equivalent residues from different sequences can be placed into the same column of the MSA. This could lead to mistaken conclusions when analysing selection data.

As we mention in the paper, this problem is avoided in most directed evolution work by simply restricting the library to be selected/screened to a single sequence length. Alternatively, when the system being engineered does benefit from using a variable-length library (eg. antibodies), sequences are grouped according to length and each of these groups is then aligned into a separate MSA. With this second approach, it could be easy to miss simultaneous enrichment or depletion of a set of similar sequences that do not share the same length.

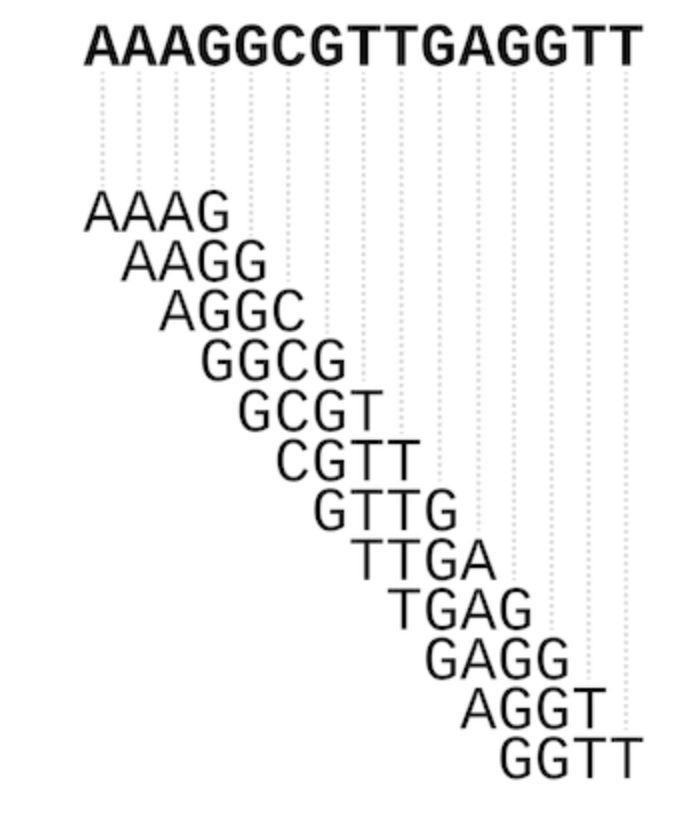

While we were thinking of ways to tackle this problem, I remembered how genome assembly tools for short-read sequencing data divide data into short subsequences, commonly called k-mers (where k equals the number of nucleotides of the subsequence), and overlaps between short k-mers are used to reconstruct much larger genomes (see scheme below).

How overlaps between short k-mers can be used to reconstruct a larger sequence, from doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw096

How overlaps between short k-mers can be used to reconstruct a larger sequence, from doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw096

While we didn’t want to reconstruct a single sequence from our selections, we thought that representing our selected sequences as sets of k-mers would allow us to compare sequences of different lengths. Our chosen representation of masked 3-mers left us with an 882-dimensional vector for each sequence, which is not the most convenient way for human eyes/brains to interpret data. So, we used Principal Component Analysis to transform the data into a lower-dimensional representation and then pick out which 3-mers were most important in each round of selection.

With this fairly simple approach, we were able to identify motifs shared by highly-performing TEM-1 sequences of different lengths, which could then be used to inform further engineering. While I did not continue pursuing this line of research after finishing the PhD, the problem of how to handle length variation in analysing evolution (natural or directed!) data without using MSAs has become a bit of a personal obsession and I’m always happy when new work appears that seems relevant!

Will deep learning models replace the MSA?

In my first industry position after the PhD (LabGenius, UK, 2017-2019), I came into close contact with the emerging field of machine learning methods applied to protein engineering. Most of this work still used aligned protein sequences as input to the models, since this makes it easier to detect structural contacts and other coevolutionary signals as interactions between columns in the MSA. However, some preprints started coming to my attention around mid 2019 that seemed to offer some interesting alternatives to MSAs for various types of sequence analyses.

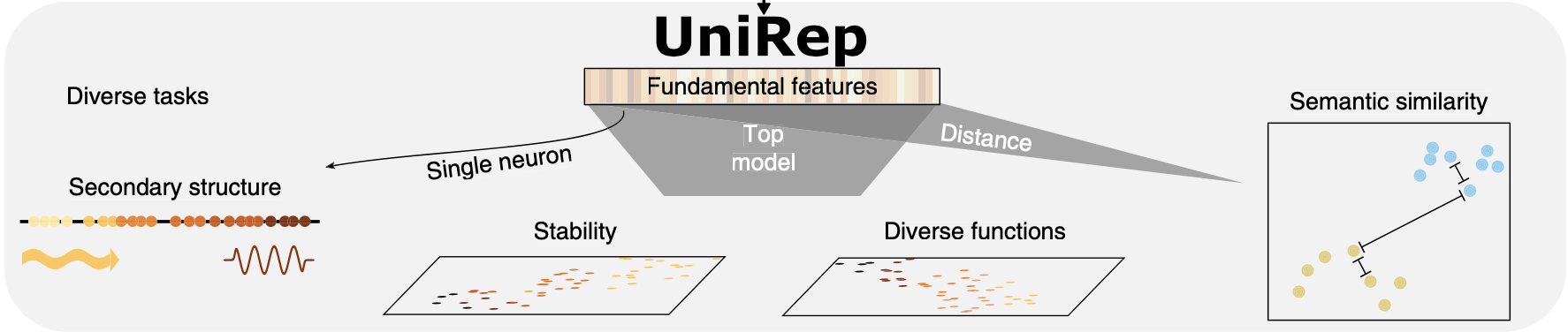

First, was Unirep from Ethan Alley @ George Church’s lab (Harvard/MIT), which is a model** produced by training on 20 million unlabeled and unaligned protein sequences from Uniref50. Once trained, this model can turn an input protein sequence into a high-dimensional vector representation that contains information about structure, evolution and function and can be used for direct comparisons between proteins with distance measures (see scheme below). Surge Biswas and the other Unirep authors also went on to show that the sequence representation produced by Unirep can be used in place of the actual sequence of a protein for supervised training of models to predict effects of mutations, using experimental data as labels. The representation/embedding generated by Unirep allows the supervised model to achieve high performance with smaller amounts of data than would be required to train a standalone supervised model on labeled protein sequences.

The embedding produced by UniRep contains structural, functional and evolutionary information on the target protein and can also be used to train supervised models, from doi: doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0598-1

The embedding produced by UniRep contains structural, functional and evolutionary information on the target protein and can also be used to train supervised models, from doi: doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0598-1

Not long after, I saw a preprint from Alex Rives at Facebook Research with a similar model to UniRep, but trained on a set of 250M unlabeled and unaligned sequences and with a different architecture, also claiming to recover relevant information from proteins using the model. Since then, various other academic groups and companies published similar work and it has been hard to keep up with how the field developed!

One more recent study that caught my attention was the one by Jung-Eun Shin at Deborah Marks’s lab at Harvard. In this work, they trained models on unaligned sets of sequences from protein families and could use the models to predict mutation effects. Since these models are generative, they further tested them by producing a relatively small library of ~200k nanobody sequences with length-variant sequences that outperformed a rationally-designed synthetic library containing more than 10^8 variants!

My question at the top of the section is a bit facetious, but I am genuinely excited to see that so many groups are now producing work that can help tackle the problem of handling length-variant sequences that seemed somewhat neglected back in 2015! Some of the models I mentioned in this post were just made available as part of a package aiming to make these models more accessible to a wider range of researchers. Since I don’t have the time nor the money*** to retrain these models just for fun, I’ll probably spend some time testing the models available on this package as a way to get started in the world of protein sequence embedding.

Footnotes

* We started developing the method in late 2015, first presented it publicly at the SynBio UK conference late 2016 in Edinburgh, and the first version of the bioRxiv preprint was posted in April 2017.

** I won’t go into details on the actual models, because there are many diferent architectures used for similar tasks and I haven’t had the chance to test any of them yet, so I don’t really have an opinion on how they actually differ in practice.

*** For instance, UniRep’s final model took >1 week to train on multiple very pricey GPUs. And I’m sure they used those GPUs for several months before landing on the published iteration of the model.